Undine: Architecture and Myth in Berlin

Undine is an exquisite and hypnotic reimagining of the Undine myth set in modern-day Berlin.

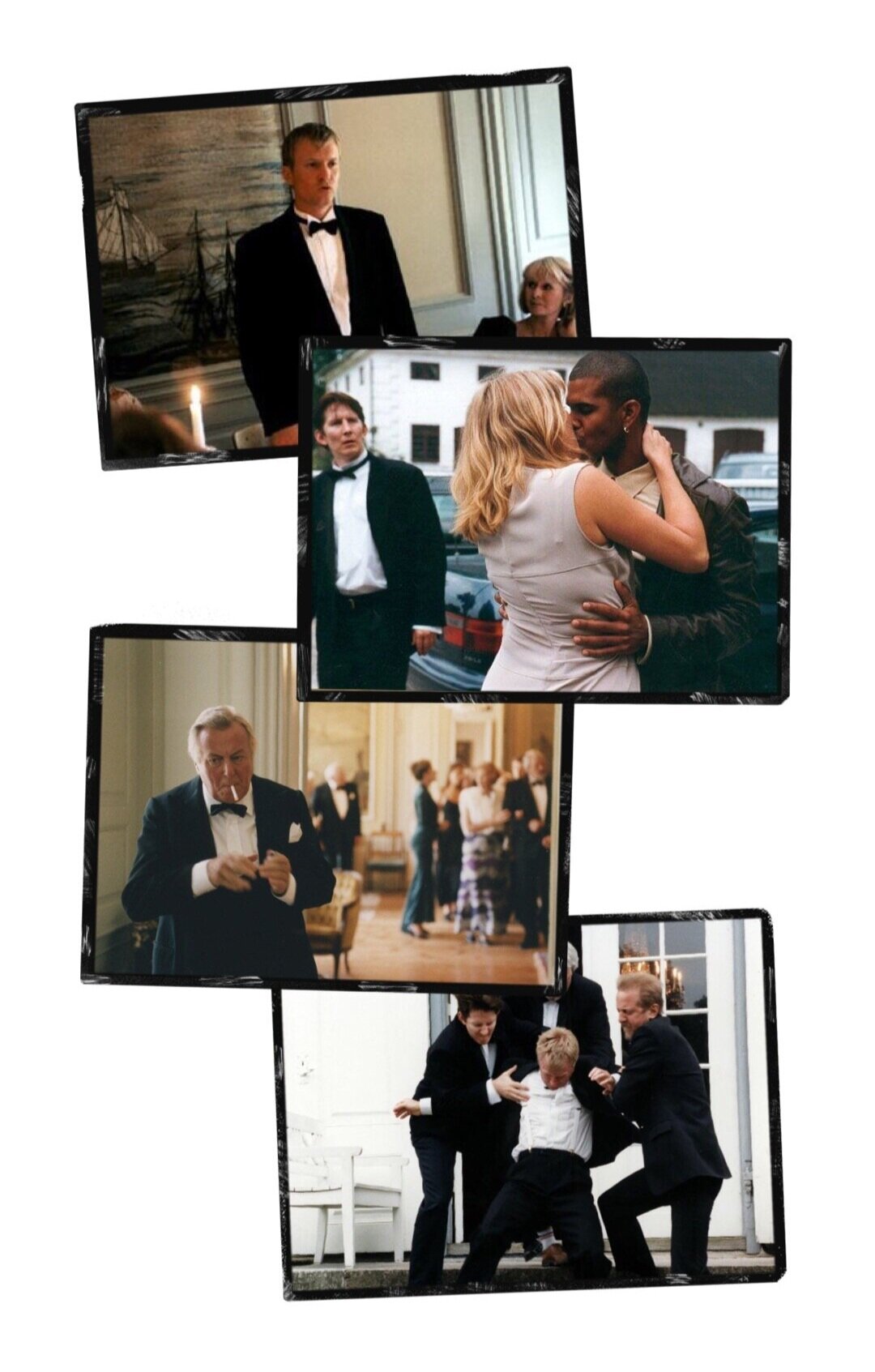

The German romantic drama film is by one of the countries most celebrated directors, Christian Petzold and stars critically acclaimed actors Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski as lovers, Undine and Christoph. Undine had its premiere at the 70th Berlin International Film Festival, where it was shown in competition for the coveted Gold Bear Award. The film ultimately secured Beer with the Silver Bear for Best Actress for her mesmerising performance as a reluctant water nymph.

In Undine, Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski are reunited with their Transit director, and let me say this trio is magical. The chemistry between Beer and Rogowski is electric here, and I found myself completely enamoured by Undine and Christoph’s courtship. They may have a semi unbelievable first encounter where a fish tank shatters, but it certainly is an enchanting one, and that’s down to the way Petzold shoots the moment. It’s a moment full of whimsy, but it juxtaposes nicely with the rather unfortunate breakup Undine suffers at the beginning of the film.

Petzold himself said in an interview with Indiewire, “As the water pours over them, they’re lying next to each other like on a beach. They open their eyes like a rebirthing scene, wet with mud and old fish. They look at each other, and the first thing they see are the eyes of the other. That’s a good start for a love story.”

I also like the fact that their courting after this almost magical first encounter takes place in ordinary and unremarkable places, which Petzold does deliberately. In a talk with fellow German director Heinz Emigholz and NYFF program director Dennis Lim, he said he didn’t want to film the love story in romantic locations. Petzold instead opted to use ordinary spaces so that the romance can ‘bewitch’ these places and transform them from something banal to something other. He also refers to a line from a poem by Joseph von Eichendorff that inspired him ‘Schläft ein Lied in allen Dingen’ (A song sleeps in all things), which I think is a rather beautiful sentiment. You can certainly see this idea has been considered throughout the movie (and in his other films too).

The other striking thing about the use of place in the film is the links to architecture and Berlin itself. Undine is a historian who gives talks about urban development, which on its own is pretty cool. But when she talks about the city’s origin, she mentions the etymology of Berlin’s name; it means ‘swamp’ or ‘dry place in the swamp’. Therefore the city like Undine has a connection to water that has been severed, and she has, in a way like Berlin, been urbanised, transformed and separated from her elemental origin. Later in the film, she rehearses a talk in front of an enraptured Christoph (such a beautiful moment!). There she talks about the Humboldt Forum, a 21st-century museum in the centre of Berlin that was modelled on an 18th-century building that once stood in the exact same place and an architectural theory that suggests that progress is impossible. A neat bit of foreboding, which is mirrored in Petzold’s cyclical direction which features recurring motifs of mysterious Catfish sightings (more on him in a minute!) and characters returning to the same locations in search of evidence of events taking place.

Another of my favourite moments in the film is where the shot of Undine looking over Christoph’s shoulder for the poster originates. It’s simple; we follow the two as they wander along in each other’s arms, as if completely smitten and unable to be separate from one another’s embrace for any length of time. The music and the atmosphere is beautiful until Undine sees Johannes, her previous boyfriend, with another woman. The camera then sweeps around to follow them walk past, and Undine peers over Christoph’s shoulder. This signifies a turning point in the film and that despite her growing bond with Christoph, her fate is catching up to her.

“Du kannst nicht gehen. Wenn du mich verlässt, muss ich dich töten”

“You can’t go. If you leave me, I’ll have to kill you“

So let’s talk about Gunther the catfish. He’s named after a character from the Nibelungenlied an Old Germanic text, very much like The Prose Edda and other mythological/legendary tales from medieval times. This little literary reference adds another texture of myth and mystery to the setting of the water, which as a dam is a natural place that has been industrialised. It’s an archaic place that has been transformed and acts as an intersection between the modern world and the world of mysticism, note that both Undine and Gunther reside there. This also connects back to the original romantic story by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, the river is so imposing in the novella that it strands characters for a period of time, however here in the modern age man has tamed the river. Petzold said in an interview that people are becoming distant from the myths and legends of the earlier years and this setting most definitely suggests that and offers us the chance to reflect on this fact.

In conclusion, I think I have found a new favourite in Undine. I love unusual romances that are sprinkled with magical realism and a sobering dash of doom. I love the performances by Beer and Rogowski, and I think Petzold has crafted such a beautiful film with so many textured layers to unpack. On the first watch, it is a whimsical love story; on the second watch, it's a meditation on time, place and autonomy…I can only wonder what a third watch will have in store for me. But ultimately, it's the intertwining of love, architecture, poetic doom and mysticism that makes Undine a film that will keep me coming back re-watch after re-watch.